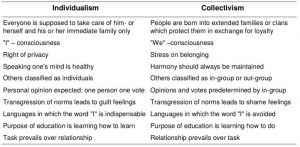

Our cultural backgrounds inevitably impact our behaviors, cognitive processes, and values, so understanding key themes within cross-cultural psychology is an important part of understanding diverse groups. Cross-cultural psychology, especially in relation to organizational and social psychology, can be especially interested in the concepts of individualism and collectivism as poles on a spectrum for cultural norms. The two concepts are useful for comparisons across different cultures, but they represent relative landmarks of complex social dynamics that do not fall into neat binaries. Generally speaking, individualistic cultures center on personal traits and independence to define self-concept, valuing individual rights, expression, privacy, and opinions¹. Collectivist cultures, on the other hand, prioritizes a sense of group consciousness, interdependence, loyalties, and community harmony, where self-concept is defined by relationships with others and in-group/out-group belonging¹. The following table¹ summarizes this dichotomy, though it is an increasingly imperfect one as cross-cultural integration becomes more common.

This blog will review the historical evolution of individualistic and collectivistic societies, as well as cultural context around each. It is also important to discuss how these ideas materialize in contemporary psychological theory, from Rogers to Vygotsky. Further, by comparing the advantages and pitfalls of each cultural dynamic, it can allow us to better cater to the mental health needs and belief systems of those coming from unique backgrounds. Finally, since individualistic and collectivist cultures have mingled more than ever, it is important to survey the current state of cross-cultural psychology, highlighting increasing intersections and the implications of this blending in daily life.

The development of individualist and collectivist societies can be seen in different pockets of the globe across history. Geert Hofstede’s research on IBM employees around the world suggests that many belief systems and values are shaped by industrial economic development2. The more industrialized an economy gets, the more individualistic the people within it, as this industrialization fosters the creativity and innovation of individuals2. Max Weber argued that individualism was also molded by the Protestant ethic of Calvinism, which advocated for self-directed morality in behavior and thought, as each individual was responsible for their own truth-seeking and inspiration4. Less economically developed regions, in his theory, are considered to be more collectivistic, relying more on the agrarian or hunter-gatherer dynamics that prioritized interdependence3. This, however, should be nuanced by the rice theory of cultural development, which considers that, even within agrarian communities, the more labor-intensive a crop, the more collectivist the culture reliant on it. For example, the namesake rice paddy crop requires careful coordination and irrigation practices that sow interdependence and cooperative labor exchange between farmers, as opposed to wheat farming, where plots could easily be managed with farmers acting as individual units. Wheat tends to be less labor intensive, aligning with the lifestyles of individualistic societies where there may be less impetus on collaboration. It is also worth mentioning that Hofstede’s research generally aligns with the framework of WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) cultures and may not account for variability in the definitions of economic development in non-Western societies2.

The understanding of this dichotomy, from a psychological standpoint, has certainly evolved and taken new forms over time. In Maslow’s understanding of human motivations, each individual is propelled by their desire to fulfill their inherent potential, commonly understood in his hierarchy of needs and motivations as “self-actualization”, with the operational unit being the individual5. Self-actualization inherently counters the ideas of collectivism as it places the individual as the point of reference for growth, rather than the goals of a larger community an individual belongs to or benefits from. This makes sense given the development of his theory around need fulfillment and human motivation emerged in the context of a highly individualistic American culture. However, embracing the diversity in behavioral drivers across cultures is an essential consideration, especially in therapeutic settings where motivating behavior change and personal development may not look the same for everyone. Another humanistic psychologist, Carl Rogers’ approach to human motivation lies somewhere in between individualism and collectivism, claiming the self is developed relative to others, but that each personal experiential field, a person’s fluid private internal world, can only fully be understood by that individual6. This may not apply as strongly for those who come from collectivist cultures, where those within a close in-group are thought to be a central part of a person’s identity and understanding of self.

Other theorists strike the chord of more collectivist cultures. These would include psychologists like Lev Vygotsky, whose theory on sociocultural development is especially of interest to developmental psychologists7. He emphasizes the role of a most knowledgeable other in defining the cultural lens of a growing child, by which adults teach youth what is culturally valued7. Relative to Piaget, who centered the process of self-motivated discovery and inquiry in children, Vygotsky discusses collective social contributions to learning. Circling back to the contributions of Hoftstede, cultural dimensions theory can be applied in a collectivist lens as members of certain groups form values, preferences, and mannerisms based on dimensions of their culture2. Each of these theories and their contributors hold implications for the functioning of community mental health. By approaching unique cultural dimensions with a tailored approach, mental health needs can be better tailored to the values someone may place on their own personal traits, independence, and self-motivated discovery, relative to their relationships as a part of themselves, their sociocultural influences, and their ingroups.

While any absolute dichotomy when it comes to the mental health of various cultures is likely misguided, it can be useful to theoretically consider the unique positive and negative effects of each outlook, leaving room for variation in individual experiences. For example, those influenced by cultures with high individualism may have an easier time investing in their own personal growth, caring for their self-esteem, and growing unique personal skill sets and expression8. These can be adaptive in therapy contexts where someone is working to strengthen their own sense of self-confidence. On the other side of this, grounding one’s identity in individual values can come with a pressure to be successful in that role, which can exacerbate isolation and stress related to self-identity.

In collectivist cultures, where the individual self takes the backseat, advantages like strong social support, community belonging, and sharing responsibilities can improve mental health. In terms of depression risk, for example, social support networks can be a significant protective factor that can be easier in collectivist cultures. When collectivism is extreme in a culture and there is a pressure to conform to social norms, this can result in a loss of personal identity or a vulnerability to peer pressure that may make mental health needs hard to recognize. Further, collectivist cultures may be more harsh towards deviation from socially normed behavior, which can contribute to stigma as it relates to mental health issues.

A unique situation may unfold at the intersection of these two cultural poles, particularly during immigration and other processes of cultural diffusion. Many immigrants born in culturally collectivist societies, generally African and Asian cultures, encounter challenges in assimilating to individualistic cultures, generally North American and Western European9. This cultural tension between community identity and the increased importance placed on personal characteristics can manifest during education, at work, and in social interactions. For example, a person from a collectivist culture with strict, hierarchical social norms may find it hard to speak up during a discussion within an individualist context where each person is expected to raise their own points and express conflicting ideas, which would otherwise be interpreted as confrontational8. As social media and increased connectivity adds to globalization trends, there are increasing opportunities for cultural exchange, presenting new challenges and opportunities for a blending between individualistic and collectivistic values.

References:

- https://www.afsusa.org/study-abroad/culture-trek/culture-points/culture-points-individualism-and-collectivism/

- https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/2020/07/31/the-paradox-of-individualism-and-hierarchy/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-44770-w#:~:text=The%20rice%20theory%20of%20culture,collectivistic%20than%20wheat%2Dfarming%20cultures.

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137034014_12

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302516151_Maslow%27s_Theory_of_Human_Motivation_and_its_Deep_Roots_in_Individualism_Interrogating_Maslow%27s_Applicability_in_Africa

- https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Psychology/Culture_and_Community/Personality_Theory_in_a_Cultural_Context_(Kelland)/08%3A_Carl_Rogers_and_Abraham_Maslow/8.02%3A_Carl_Rogers_and_Humanistic_Psychology#:~:text=A%20person’s%20needs%20are%20defined,actualization%20(Rogers%2C%201951).

- https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html

- https://hilarycorna.com/the-culture-of-the-future-collectivism-vs-individualism/#:~:text=A%20collectivist%20culture%20looks%20like,of%20cooperation%20and%20increased%20conflicts.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4711941/