Many specialties within medicine have been recently moving toward personalized approaches, often termed “precision medicine.” This term, often used with descriptors like personalized medicine, person-centered care, or stratified medicine, was coined in 1997 when Thai researcher Dr. Prawase Wasi described the potential impacts of growing knowledge around human genomics [1]. Amid the rapidly developing effort to map all 30,000 nucleotides of the human genome at the time, his article discusses how this database will open up possibilities for highly precise tools for research, screening, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. The way that the fields of predictive or preventive medicine and precision medicine utilize these innovations has broad social implications, especially as they relate to the field of psychiatry. While this initial view of precision medicine took on a perspective primarily centered on genetically-informed care, precision medicine can also be modelled as broader than this, integrating components of the biopsychosocial model of health [2]. Applications of precision medicine in psychiatry may seek to tailor medical treatments to the individual characteristics of each patient, taking into account genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorders, are complex and multifactorial, involving a combination of genetic, environmental, psychological, and neurobiological factors. Therefore, psychiatry may be a field uniquely positioned to benefit from such treatment approaches, especially given the high heterogeneity of symptoms within individual disorders [3].

What might personalized medicine in psychiatry look like?

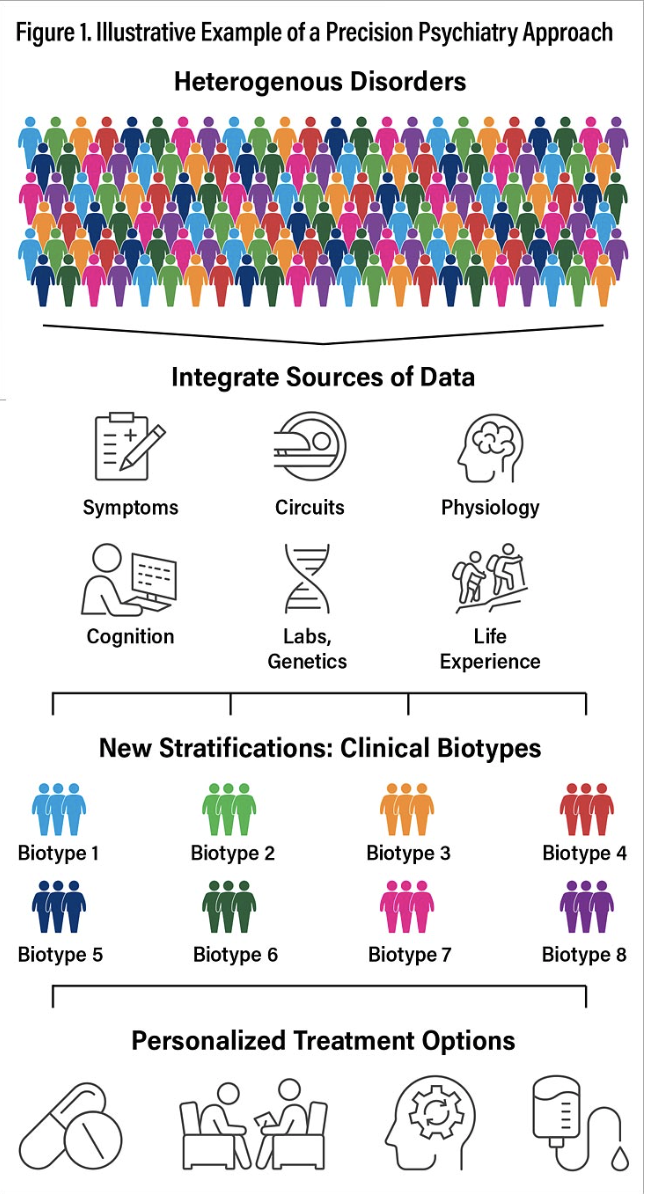

Currently, there are ongoing research areas and forms of treatment that embody the principles of precision medicine within this specialty, although the need for further progress persists. Often used in treatment plans for depression and OCD, transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation are therapies that leverage individualized neuroimaging in order to tailor stimulation to the unique neuroanatomy, connectivity, and clinical symptoms of a given patient [3]. Representing a more traditional approach to precision medicine, where psychiatry adopts the same approaches as the personalization used in other specialties, is pharmacogenomics. For example, the metabolism and efficacy, predictive of adverse drug reactions and clinical treatment response, for certain types of antidepressants can be assessed based on gene expression profiles and biomarkers often used in single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [4]. The knowledge of a patient’s unique gene expression profile may prevent adverse drug effects, reduce the likelihood for someone switching medications, and improve patients’ adherence to their medication regimen. Some even advocate for the use of machine learning algorithms to synthesize genetic and clinical data to inform clinician decision-making, although this is a developing field. The polymorphisms and drug metabolism dynamics most often associated with precision medicine also work synergistically with the consideration of unique environmental and social variables, such as childhood trauma and stress exposures [5]. Ultimately, the move towards precision psychiatry must take into account more than the purely biological, finding concrete ways to situate the role of individual patient experiences of mental health challenges within treatment approaches. The schematic below [5] summarizes one potential model for how these complex variables may play complimentary roles for designing targeted treatments. Dr. Leanne Williams emphasizes the practical benefits of such an approach in describing the scarcity of strategies for “selecting effective treatments for each individual in a timelier manner that limits the need to wait for multiple tries and failures of ineffective treatments” [7].

Potential Ethical Issues with Precision Psychiatry

While the idea of highly-tailored, individualized care is appealing for many reasons, advances in precision medicine, especially given the sensitivity of psychiatric diagnoses for many, should anticipate ethical conflicts. There are some who express concerns that drug development produces precision in the inclusion of patient profiles that are best suited for the benefits of a drug, this conversely produces targeted exclusion of those that cannot [6]. This is not at all to say that precision approaches for psychiatric care should be avoided entirely, rather clinical guidelines for the use of personalized tools should take into consideration these ethical realities. As psychiatrists or pharmacists use pharmacogenetic tests, there is a high priority on protecting the genetic information obtained, just as any other health data would be protected. The emphasis on legally safeguarding pharmacogenetic data in psychiatric practice to protect patient privacy and confidentiality has added to calls for caution to “regulate the use of genetic tests” [6].

Others emphasize the way that precision psychiatry, so far, has emphasized the role of genetics, biomarkers, and neuroimaging to adapt treatments to individual patient profiles leaves out a core person-centered aspect of care. They propose that a more ecosocial framework for precision psychiatry will capture the lifespan development, social-structural, cultural-historical and experiential aspects of mental illnesses [8]. Integrating multiple sources of data from each dimension of a patient’s life is critical in moving past one-size-fits-all approaches to psychiatric treatment plans. An alternate framework for encouraging the clinical translation of precision tools can be found here [7].

The Promise of Precision Mental Healthcare

Applying the same precision medicine tools that are used to take care of the body are as important in taking care of the brain. Just as a physician may screen for a family history of diabetes or exposure to carcinogens, assessing for family history of mental health conditions and exposure to chronic stressors or traumatic events may build out a more effective, targeted treatment plan, combining therapy with pharmaceutical interventions [9]. While precision medicine in this field is still a rapidly evolving area of study, it represents an effort to advance the equity between mental healthcare and healthcare at large, since the two are part and parcel.

Sources

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9561633/

-

https://surgery.wustl.edu/three-aspects-of-health-and-healing-the-biopsychosocial-model/

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-023-00131-y

-

https://arc.net/l/quote/iajrwmdo

-

https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-11-132\

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3181935/

-

https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.09.9.23

-

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2023.1041433/full

-

https://stanmed.stanford.edu/precision-mental-health-promise/