988 Progress So Far

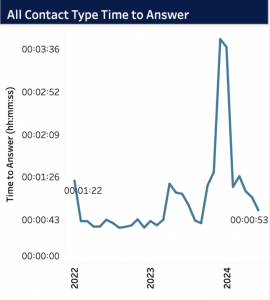

For those who work in crisis services, are advocates for suicide prevention, or have ever benefitted from the use of a crisis service, the restructuring of the national suicide crisis lifeline from a ten digit number to the 9-8-8 abbreviation was a pivotal shift. This reform was aimed at increasing ease of access to the hotline when someone might be facing a mental health crisis. With the shortened number and expanded language options, former Health Secretary Xavier Becerra states that the new service received 2 million more calls in its first year than the former helpline number had received the previous year [1]. This alone is a clear testament to 988’s increased recognizability and promotion in mental health advocacy, and it has produced improvements by other metrics. For example, between 2022 and 2024, wait times have gone down from 1 minute 22 seconds to 53 seconds, indicating improvements in the crisisline’s capacity despite increased volume [2].

Continued Barriers

Despite successes with this shift in crisis services in the US, there are still continued barriers in the mission of accessible mental healthcare. A significant concern, especially with the goal of increasing engagement from marginalized groups, is the potential for in-person or involuntary interventions as a result of calling a hotline [3]. Although in-person interventions, and involuntary ones within that category, are in the vast minority, increasing transparency around crisis protocol and the crisisline’s local partners has potential to increase trust with communities that experience hesitancy with reaching out. Maintaining consistent staffing of crisis services is another growing concern, a reflection of a larger mental health workforce shortage impacting the entire country [4]. In general, the fewer counselors on line to take calls or chats, the less quality support contacts receive. Another key hurdle to address is the activation of local services when someone reaches out to 988. Although it is a national hotline, the ability to tailor to an individual contact’s geographic location is essential in making sure the resources recommended by crisis counselors are truly accessible in crisis situations.

Georouting vs Geolocation

In a move that potentially seeks to remediate this issue, the FCC has recently adopted rules that will require all U.S. wireless carriers to implement georouting for calls to the 988 Lifeline [5]. To understand why this is such a key change, it is important to differentiate between geolocation and georouting, since they can be easily misconstrued.

| Georouting | Geolocation | |

| Main purpose: | Directs calls/messages to the right center | Determines user’s exact location |

| Data inputs: | Uses caller’s area code, IP, or GPS data | Uses GPS, Wi-Fi, cell towers, or IP |

| Example use: | Directing a 911 call to the nearest dispatch center | Sending an ambulance to a caller’s exact location |

| Potential barriers | Potential misrouted calls, if using outdated area codes | Privacy concerns, accuracy issues in rural areas |

While it has required carriers to implement georouting for calls to the 988 hotline, there are no current plans to require geolocation. It is important that 988 calls are routed geographically, since this allows for calls to be connected to a crisis center near their actual physical location. Local crisis centers will have a better understanding of accessible community mental health resources or mobile crisis units, so they are better equipped to make referrals or coordinate interventions, should that be necessary [6]. Having an active list of nearby organizations that meet various community needs, even if they are indirectly related to mental health (e.g. housing resources, food security organizations, domestic violence safe houses) can be critical in connecting contacts to longer term, more sustainable forms of support.

Further Implications and Concerns

On the other hand, geolocation is concerning to some as it would pinpoint a contact’s exact location when they reach out to a crisis line. Not only does that introduce privacy concerns, some are concerned that this might increase the risk for involuntary interventions if crisis centers are readily able to direct emergency services to an exact location. This is especially worrisome in the context of research that has reported that perceived coercion during a hospitalization for mental health led to a small, yet significant increase in the likelihood of postdischarge suicide attempts [7]. If access to precise location identification makes it easier for emergency medical services and mobile crisis units to locate individuals in active suicide attempts, others might argue that it has time-saving benefits for these worst case scenarios. It would be necessary, then, to ensure thorough mental health crisis training for first responders to avoid potential violent escalations or unwarranted nonconsensual hospitalizations [8].

Current literature makes the disparity in suicidality clear: individuals living in rural communities are at higher risk for suicide compared to urban communities. This risk has nearly doubled in the last 20 years, underscoring the need for geographically tailored crisis interventions. This feature can improve the tailoring of crisis services for remote situations by reducing distances for care and ensuring that calls from people who move around frequently are still routed to crisis centers in close proximity [9]. Georouting is one small step forward in that mission, with larger strides in mental healthcare workforce recruitment and retention needed for systemic changes. To read more about the specifics of the FCC’s policy change, find more information in this article.

Need support now? 988 offers 24/7 judgment-free support for mental health, substance use, and more. Text, call, or chat 988.

Sources

-

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/988-hotline-helped-millions-in-its-first-year-heres-how-advocates-say-it-could-reach-more

-

https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/988/performance-metrics

-

https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/challenges-to-just-and-effective-988-implementation/

-

https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/988-suicide-crisis-lifeline-two-years-after-launch/

-

https://www.fcc.gov/988-suicide-and-crisis-lifeline#:~:text=At%20the%20October%2017%2C%202024,%2Dwireless%2Dcalls%2D988.

-

https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/event/georouting-geolocation-next-steps-988/#:~:text=With%20georouting%2C%20the%20routing%20and,in%20case%20of%20an%20emergency.

-

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sltb.12560

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4294132/#:~:text=Mental%20health%20training%20is%20essential,death%20(2%E2%80%935).

-

https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/public-health-strategy/suicide-in-rural-america-prevention-strategies.html

-

https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/fcc-set-require-georouting-988-lifeline-calls-enhancing-access-local-services